As the latest judicial document on the crime of assisting information network crimes issued by the “Two Highs and One Ministry”—the “Opinions on Issues Concerning the Handling of Criminal Cases Involving the Assistance of Information Network Crimes” (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Opinions’)—comes into effect, two cases involving the use of “two cards” for assisting information network crimes, represented by Lawyer Li Wei, have successfully achieved acquittal: one case resulted in the release of the defendant, who had been criminally detained for 27 days, through the conversion of criminal charges to administrative penalties; the other case led to the police terminating the investigation against the defendant, who had been criminally detained for 30 days. Both cases relied on the comprehensive determination rules for subjective knowledge and the policy of combining leniency and strictness outlined in the Opinions.

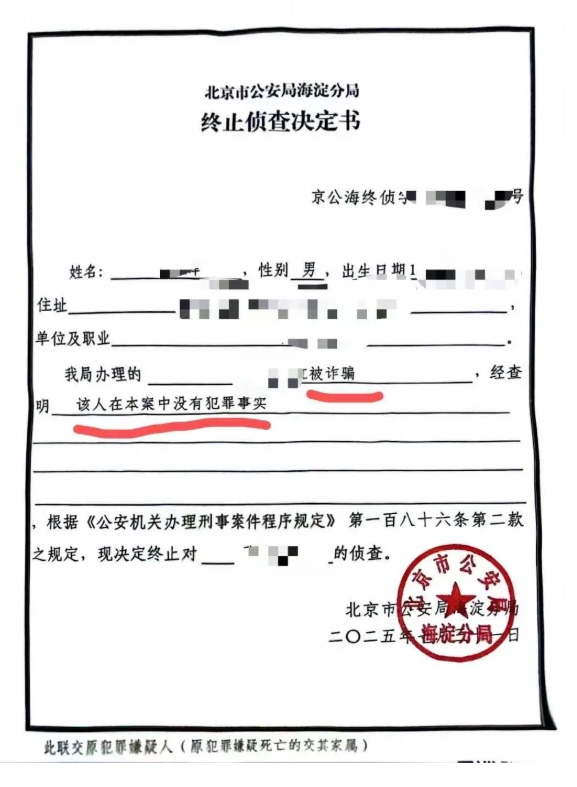

Case One

Loan fraud led to the use of a bank card, with transaction volumes exceeding 600,000 yuan,涉嫌 assisting in information network crimes. After 27 days of criminal detention, the case was transferred to administrative penalties, and the criminal investigation was terminated.

The party in this case, due to urgent need for funds, was induced by fraudsters during an online loan process to apply for and provide their personal bank card, which was later used to transfer telecommunications fraud funds, with transaction amounts reaching 600,000 yuan. Attorney Li Wei, through meetings with the defendant, thoroughly understood the case details. The complete chat records between the defendant and the fraudsters clearly showed that when providing the bank card, the defendant was only informed that it was “needed for the loan” and did not receive any abnormal compensation. Additionally, when the bank informed the defendant of abnormal risks associated with the bank card, the defendant proactively went to the bank to freeze the card, with the remaining frozen funds amounting to 530,000 yuan. Attorney Li Wei presented three core defense arguments to the public security authorities:

First, the defendant lacked the subjective intent to commit a crime, as there was no general awareness that the bank card would be used for criminal purposes. All communication records pointed to a “normal loan process,” with no mention of any illegal activities;

Second, the defendant's involvement in the case was significantly minor, the involved actions did not cause actual losses, and the defendant immediately voluntarily froze the bank card upon discovering the abnormality, preventing further funds from being transferred out, meeting the conditions for exoneration under Article 15 of the Criminal Procedure Law, which states “the circumstances are significantly minor and the harm is not significant”;

Third, in accordance with the policy of “minimizing arrests, prosecutions, and detentions,” this case is more suitable for achieving educational and punitive objectives through administrative penalties.

Ultimately, the case was converted from a criminal case to an administrative penalty case, securing an acquittal for the defendant.

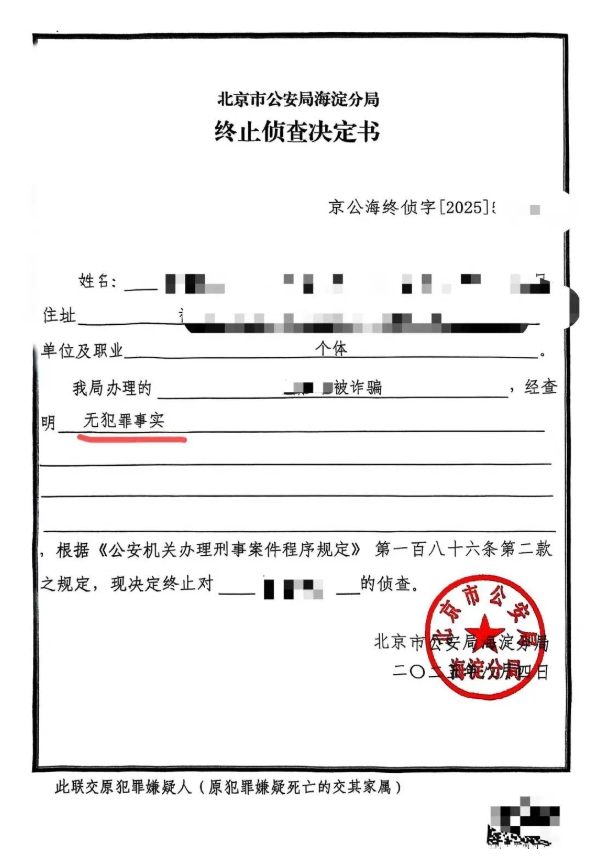

Case Two

A routine mobile phone transaction became entangled in upstream criminal activities, resulting in 30 days of criminal detention before the investigation was terminated.

In the second case, the defendant had been engaged in mobile phone retail business for an extended period. During a transaction, the payment made by the buyer was found to involve funds from telecommunications fraud, leading to the defendant's criminal detention by the police on suspicion of aiding and abetting telecommunications fraud. After Attorney Li Wei intervened, he found that the transaction process between the defendant and the buyer fully complied with industry norms:

First, the transaction was genuine, with both parties having conducted multiple transactions prior to this one and having communicated multiple times via chat software beforehand, with no abnormalities in the communication process;

Second, the buyer paid through a legitimate payment platform, and the defendant conducted the transaction in accordance with industry norms, with the transaction price aligning with market conditions and no obvious signs of purchasing at an abnormally low price.

Regarding the police's accusation of “abnormal bank card transaction records,” Attorney Li Wei argued that transaction records alone cannot be used to infer subjective knowledge; instead, they must be evaluated in conjunction with the transaction context, profit circumstances, and other factors. Additionally, the family provided transaction records demonstrating the defendant's long-term lawful operations and no history of abnormal transactions.

Ultimately, the defendant was released after 30 days of criminal detention, and the police made a decision to terminate the investigation.

The successful resolution of these two cases is not an isolated breakthrough but a vivid embodiment of the core spirit of the “Opinion.” As the latest important document regulating the judicial application of the crime of assisting and facilitating criminal activities, the “Opinion” provides clear guidance for handling similar cases through its refinement and adjustments to previous regulations. Li Wei's defense strategy and the case outcomes align with the core principles of these new regulations.

How is “subjective knowledge” determined in cases of assisting and facilitating criminal activities?

In determining “subjective knowledge,” the Opinions have broken away from the previous model of relying solely on the outward appearance of a single act to make assumptions. Instead, they emphasize the need to comprehensively assess the individual's cognitive abilities, professional status, and communication records. Additionally, the Opinions have introduced new presumptive scenarios for professionalized acts of assisting and facilitating criminal activities—but explicitly state that “the opposite applies if there is contrary evidence.” In the first case, the complete chat records between the defendant and the fraudsters clearly showed that the defendant was only aware that the bank card was needed for a loan and had no knowledge of any criminal activity, thus lacking “subjective knowledge,” which aligns closely with the Opinion's requirement to “avoid objective attribution of guilt”; In the second case, the defendant's long-term legitimate business records of mobile phone transactions and normal market price transaction documents with buyers sufficiently prove that they were unaware of the involvement of the proceeds in upstream criminal activities, directly corresponding to the “comprehensive consideration to exclude reasonable doubt” logic in the Opinions, ultimately leading the investigative authorities to acknowledge their lack of criminal intent.

How should the standard for “serious circumstances” be interpreted?

Regarding the standard for “serious circumstances,” the Opinions' adjustments further emphasize the orientation toward “precise criminalization.” They not only refine the quantity and standards for crimes involving “two cards,” but also establish the principle of “two-way verification”—first verifying whether the criminal amount of the assisted party meets the relevant criminal standards, avoiding a blanket approach based solely on transaction flows. In the first case, although the 600,000 yuan transaction volume far exceeded the “200,000 yuan” standard under the old regulations, the Opinions' emphasis on the “association between transaction volume and criminal activity” allowed the circumstances of “no severe losses caused + proactive damage control” to be considered, providing a basis for the case to be downgraded from criminal to administrative penalties.

The leniency and strictness in the Opinions

In terms of implementing the policy of combining leniency and strictness, the Opinions' tiered governance approach is particularly evident: on one hand, it clearly stipulates stricter penalties for organizing minors, industry “insiders,” and cross-border crimes; on the other hand, it provides for lenient treatment for circumstances such as “being deceived into participating,” “short-term gains,” and “pleading guilty and accepting punishment,” with a stronger emphasis on “education first” for minors and students. In the first case, the defendant was “deceived into providing a bank card,” had “no illicit gains,” and “proactively reported the loss and filed a police report,” fully meeting the criteria for leniency under the Opinions. The application of administrative penalties instead of criminal prosecution is a concrete manifestation of the principles of “minimizing arrests, prosecutions, and detentions” and the coordination mechanism between administrative and criminal enforcement.

Additionally, the Opinions' rules for distinguishing between the crime of assisting and facilitating criminal activities and related crimes provide a basis for accurately determining the nature of the case. It clearly defines the boundary between the crime of assisting and facilitating criminal activities and the crime of concealing or hiding proceeds of crime as “subjective knowledge of the content” and “the stage of the assisting behavior”—the former refers to assistance and support during the commission of the upstream crime, while the latter refers to the handling of proceeds after the crime has been completed. In both cases, the parties had no intent to participate in the upstream crime or handle the proceeds of crime, and their actions were limited to “providing an account” or “normal transactions.” There was no collusion or stable cooperation with the upstream crime, thus ruling out the possibility of related crimes. This is fully consistent with the requirement in the Opinion to “accurately determine guilt and impose appropriate penalties, ensuring that punishment aligns with the severity of the crime.”

Attorney Li Wei stated that there are no minor criminal cases; every criminal case requires utmost effort. The breakthroughs in these two cases fundamentally embody the core logic of the Opinions' “precision targeting of crimes and protection of legitimate rights and interests.” By thoroughly studying the key points of the new regulations and employing precise defense strategies, the warmth and rigor of legal provisions are transformed into tangible rights and interests for the parties involved, making judicial fairness clearly evident in every case. The new regulations, by refining recognition standards, clarifying boundaries, and distinguishing tiers, not only strengthen deterrence against organized and professional assistance-related criminal activities but also reserve legal space for ordinary citizens and legitimate business operators who have been coerced or exploited.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)